A Painter of the Holocaust for Our Times

Three self-portraits by Felix Nussbaum, at New York’s Neue Galerie

Published in Tablet Magazine, June 2019 — View Hebrew translation

A couple of weeks ago I visited the Neue Galerie to see The Self-Portrait. I knew there were some small etched self-portraits by Rembrandt from 1629-30 and, another favorite, the marvelous Max Beckmann “Self-Portrait with a Horn.” After going through the exhibition, on its final wall I saw them—three self-portraits by Felix Nussbaum. Coincidentally, at the same time I was reading Timothy Snyder’s important and disturbing book, Black Earth. Looking at Nussbaum’s three self-portraits the other day I saw the horror—dispossession and depersonalization leading to mass murder—that I’d just been reading about.

Felix Nussbaum was born in Osnabruck, Germany, in 1904, a bad birth year for European Jews. He came from an art-loving background; his father, who served as a soldier in World War I, had been an amateur painter before he had to support a family. But, from an early age he encouraged his son to paint. When Felix turned 21 he moved to Berlin, where he studied painting at the Lewin-Funcke School. At 28 he won a one-year award to study painting at Rome’s Villa Massimo. (It was one of two scholarships awarded by the German government to art students in 1932.) As a former art student myself, I understand how thrilling that must have been for Nussbaum. He worked for the first year in Rome, but had to leave suddenly the following year, 1933, when Hitler and the National Socialist party came to power. That same year, his studio in Berlin was set on fire, destroying all the art he had there.

In 1937, Nussbaum and his companion, Felka Platek, left Germany and moved to Belgium. In 1939, Nussbaum had a solo exhibition in Brussels—his last.

Late in May 1940, Hitler captured Belgium. Felix was almost immediately arrested in his apartment and transported to an internment camp at Saint-Cyprien, where 7,500 German Jews were taken in 1940. Nussbaum remained there nine months, then escaped. He was able to board a passenger train to Brussels where he spent the next four years painting, hidden in an apartment provided by Belgian friends. At first, he painted on the top floor, but then, concerned that the turpentine smell would reveal him to SS officers on Jew hunts, his friends arranged a basement studio.

‘Self-Portrait in the Camp,’ 1940, oil on panel (Photo: Hulya Kolabas for Neue Galerie New York © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

“Self-Portrait in the Camp,” from 1940, is a remembered image of Nussbaum’s nine-month experience in the Saint-Cyprien camp. The painter is now a snarling ecce homo—Nussbaum transformed into inmate. He wears a torn and tattered shirt and a strange cap. Behind him a bare-assed woman defecates into a steel drum. As the WWII Polish writer, essayist, and underground fighter Gustaw Herling-Grudzinski wrote, “A man can be human only under human conditions.” Clearly these were not that.

Not since Isack van Ostade in 1641 had there been someone shown defecating in a painting. In the late 15th century Bosch had painted naked behinds with things sticking out of them, but not the actual act. In the Nussbaum, to the left of the main figure, a dejected man with his head in his hands sits at a table. The overall image is small, dark, and confined. Barbed wire appears at the horizon signifying there is no way out. A few scattered bones lie on the desert-like earth.

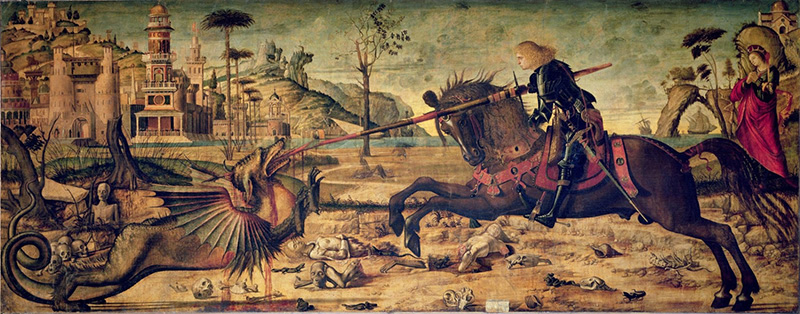

As often happens, this picture triggered another association in my mind, a canvas I’d seen in 2007 on a trip to Venice: Vittore Carpaccio’s “St. George and the Dragon” at Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni.

Vittore Carpaccio, ‘St. George and the Dragon,’ 1502 (Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice)

This large horizontal painting is ostensibly about St. George slaying the dragon. But I became fascinated by the lower section (this area happened to be level with my eye as well) which showed dismembered body parts. At the time I was interested in the discrepancy between the fancy-clothed figures and the horror on the ground. Nussbaum’s painting is a boiled-down version of the Carpaccio, but the desolation and inhospitality of the foregrounds are the same in both pictures.

The second of the three Nussbaums at the Neue Galerie is “Self-Portrait in a Shroud,” from 1942. Frankly, I was annoyed to learn the Berlinische Galerie owns the picture, because it is in the same city that burned all his artwork in 1933. The same country that even now is slow to return stolen paintings to the heirs of the Jewish families who had collected them. Why should this painting about his enforced racial confinement be proudly displayed in Germany?

‘Self-Portrait in a Shroud (Group Portrait),’ 1942, oil on canvas (Berlinische Galerie – Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst, Fotografie und Architektur. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

In the picture, a handsome, youngish man holds a sprig of green leaves in his left hand. Does this represent his longing for nature, the memory of former walks among trees and flowers now no longer possible for a Jew like him? The picture with its large red door on the left and closed blackened window is claustrophobic. (The black window tells it all: sunlight will not enter here, nor air, the window cannot be opened.) The picture’s composition with its central axis, and muted palette reminds me of Titian’s ‘Allegory of Prudence’, in the National Gallery, London.

Unlike “Self-Portrait in a Camp,” here Nussbaum turns his face, with its troubled expression, away from the viewer. His brow is prematurely lined. The standing male figure above is cropped at the eyes, already dehumanized. His skin has turned an unhealthy yellowish tone. The rope in his hand suggests hanging. Is this the shroud of Nussbaum’s title? The figure’s open mouth can serve either as a sign of shock, or an attempt to emit an inhuman sound. Is he about to kill himself?

The female figure to the right seems to think so. As if protecting herself from what is to come, she holds her hand near her eye, while the other woman to the left looks almost longingly at the shroud-like man.

Nussbaum’s canvas is a thick Belgian linen that allows the viewer to see its rough weave through the paint. Unlike the “Camp” picture, which has several layers of paint, this one is thinly coated. In the background the color shifts from dark brown to a more reddish hue. Borrowing from the smooth surfaces of early Netherlandish art, Nussbaum’s technique is flawless. Despite being locked in a room where at any hour that fateful knock on the door might occur—it had already happened once—the painter is still able to focus and achieve this picture.

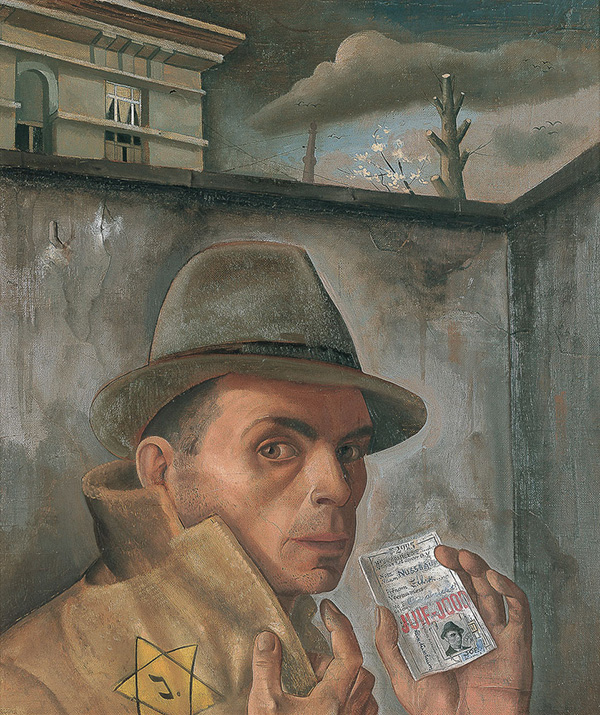

A third self-portrait at the Neue Galerie is perhaps the most subdued. In “Self-Portrait with Jewish Identity Card,” from 1943, Nussbaum looks frightened. His tan coat casts a sickly pallor over his skin. He wears a period hat, like the ones I remember my father wearing in the early 1940s. The monochrome gray colors surrounding the figure bespeak gloom and depression. Indeed, the whole picture has the quality of a bad dream. The enclosing wall, the small birds overhead, the heavy ominous cloud, crossing electric wires, the one tree in bloom—nothing good will take place here.

‘Self-Portrait with Jewish Identity Card,’ circa 1943, oil on canvas (Photo: Museumsquartier Osnabrück, Felix Nussbaum Haus. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

The painter has changed. He no longer looks angry, or lost in thought, but rather beaten and afraid. Standing in front of the picture at the Neue, I looked right into the portrait’s eyes. They looked haunted, as Nussbaum must have been then—locked up for three years with no end in sight.

His identity card says Jew in two languages, Dutch and French. That is his crime! Whatever he believes, whatever he does, he’s been branded by the card and the Star of David drawn on his coat. And this will be enough to end his life. The feelings of that time are embedded in the very warp and weft of the canvas. It is frozen time.

Snyder tells his reader that as a German citizen Nussbaum had a better chance of surviving. Hitler very carefully and strategically set out to remove citizenship from Jews to render them outside of the laws—stateless, where no rules pertained. All the Jews in Poland, once Hitler took over that country, had no citizenship. Anyone could take their property, their money, and eventually their lives because they were a minority and there were no laws protecting them. Many Poles and Russians immediately did that, took over the homes, possessions, and, where possible, the money of the displaced and murdered Jews. Most Russian and Polish Jews did not survive, but about 40% of German Jews did. Snyder tells us, “Jews who were German citizens were much more likely to survive than Jews who were citizens of states that had been destroyed.” And Jews living in Belgium had a 60% survival rate. Unfortunately, that wasn’t true for the Nussbaums.

In the late spring of 1944, it finally happened—the second knock on the door. As with Anne Frank in Amsterdam, an informer turned the painter and his wife in. Nussbaum and his wife, Platnek, were on the last train out of Brussels, going to a transit camp at Mechelen and then to the killing factory of Auschwitz-Birkenau, where they were murdered in August 1944. The liberation of Belgium on Sept. 3, 1944, came too late for the artist and his wife, mother, father, brother, and sister-in-law, all of whom were wiped out.

Yet Nussbaum’s paintings exist! He got to tell the story of what it was like, what he endured at the hands of the Nazis. As Nussbaum wrote, “If I disappear do not let my paintings die.”