Paintings about painting

On “Americans in Paris: Artists Working in Post-War France, 1946–62,” at the Grey Art Museum, New York.

Published in The New Criterion, June 2024.

It was a treat to enter the Grey Art Museum’s “Americans in Paris: Artists Working in Post-War France, 1946–62” (on view through July 20). Taking in the museum’s first room, I immediately noticed that the pictures carried no didactic messages, were neither politically correct nor incorrect, and had no relation to racial or gender diversity. What a relief!

Similar to the abstract expressionist painters working in New York during the same period, these artists were primarily concerned with painting itself. The exhibition reflects this, bringing to our attention the diversity of color in chiefly abstract pictures. The show consists of 130 paintings, sculptures, photographs, films, and textiles by close to seventy American artists who worked in Paris. As a painter myself, I’ll be focusing on the exhibition’s paintings.

The migration of writers and artists to Paris after World War I is well known. The city was a “moveable feast” during those years, in Hemingway’s words, and through the process of osmosis these writers and artists were changed by and changed the city itself. Things were more difficult in the years following World War II. As Janet Flanner wrote in her journal, “All of Europe, France included, is sick, weak, and physically and morally hungry.” But that didn’t prevent American artists from coming to Paris, many of whom were funded by the GI Bill. Even as Paris was in shambles, there remained an outstanding cultural and artistic legacy to draw from. And many of these artists left a mark of their own on the city.

I stopped first at a group of early Ellsworth Kellys. These three medium-sized canvases are almost sui generis, although one clearly references Mondrian. Kite I (1952) is composed of five short panels, yellow and white, and a center panel that is broken down into squares of blue, black, and red. Placing the three strongest colors at the picture’s center destroys its “overallness.” Nevertheless, Kite I has a strong presence on the wall.

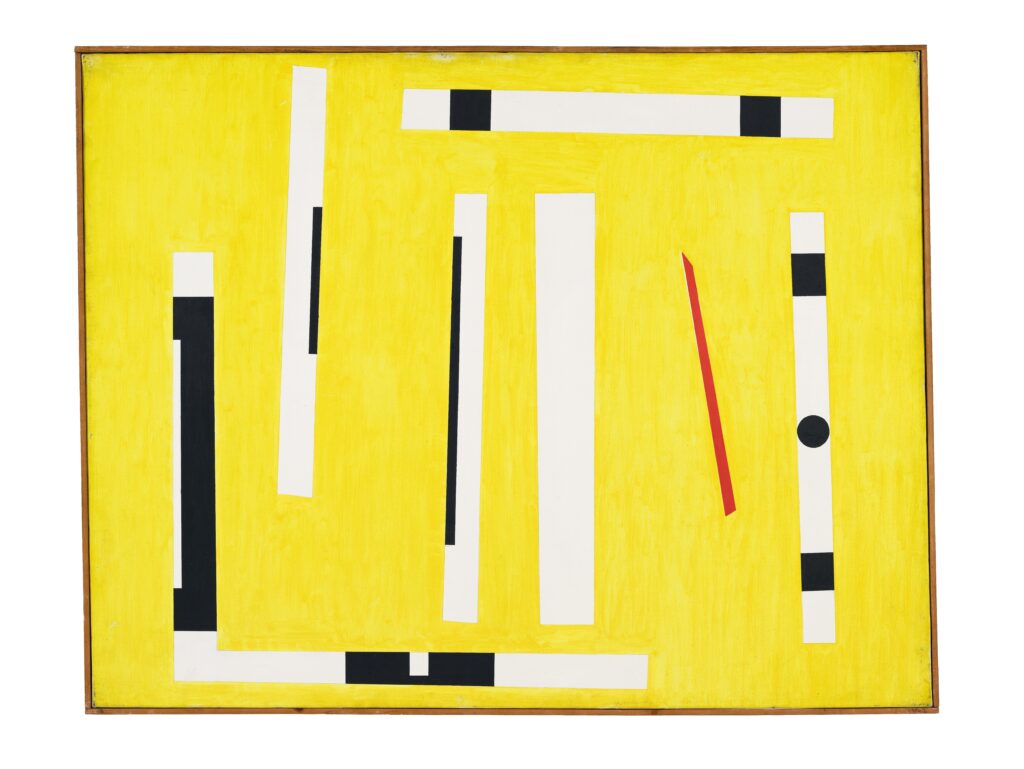

Fond Jaune (1950) is convincing—and surprising in Kelly’s oeuvre. On a very delicate pale-yellow ground, the painter placed long white rectangles with small squares, circles, and thinner black vertical lines inside. This is an “enclosed space” picture: none of the bands extends to the canvas’s edge. A small, slanting, thin red bar leans precariously on the right side of the painting but somehow does not disrupt the surface tension. Kelly remained in Paris until 1954. His years in France were critical to his aesthetic maturation.

Kenneth Noland is a painter I knew personally, and his art influenced my early stain paintings. In fact, we both exhibited at Andre Emmerich Gallery in the Seventies. I had not been aware that Noland painted in Paris from 1947 to 1950, studying with Ossip Zadkine. Three small oils from this time are shown here; they are very different from his signature work. In fact, I didn’t immediately identify them as his. In the two smallest, Untitled (1947) and Untitled (1950), I saw Paul Klee and perhaps a little Joan Miró—especially in the 1950 work. The third work on display, Inside (1950), is more distinct. A thinly painted black ground surrounds chunky gem-like shapes of yellow with touches of red and blue that create a stained-glass-window look. After this period, Noland returned to Washington, D.C., where he started working with the newly invented Magna acrylic paint on raw canvas and created his breakthrough Circle series.

I’ve never liked Joan Mitchell’s work. It often smacks of self-indulgence. One rarely has a sense of the artist bearing down. Two early Mitchells, both painted in 1960 and left untitled, are a case in point. The more problematic is a large horizontal canvas made with green and black strokes that read simply as dark. Above sit three variously sized dabs of ochre. Elsewhere on the picture plane, I couldn’t help but see blackish lines configure into the shape of a dog in profile with a white paint-dot eye. This sometimes happens in abstraction: shapes will emerge to create an unintended image. But once it’s been noticed, the artist quickly paints it out. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen here. The second work is similar to the first but less energetic. It fails to become a whole image.

In the final section, three large works by Sam Francis steal the show. They’re ambitious and fully in Francis’s voice, which, apparently, he found early—he was in his mid-thirties when these were painted. My familiarity with Francis comes from his Seventies pictures, which lack the energy and newness of the works here. White Line (1958–59) is a vertical canvas in which the white priming coat of the center is splattered with delicate touches of color—blue, yellow, red, and magenta, for example—coming from both the left and right sides. In places, Francis uses the Fauve device of separating the colors with narrow white spaces, and he leaves a purer white priming-coat area in the center. It thus presages Morris Louis’s Unfurled paintings of 1960–61. Francis was a success in Paris.

The last room also held two of Shirley Jaffe’s early abstract pictures. In the Nineties, I was in Paris often and met Jaffe, who never left Paris after moving there in 1949. On a couple of occasions, I trudged up five flights of stairs to her studio in a charming old Montparnasse building. Her later works are clear and bright in Stuart Davis–like jazzy colors. The works in the show are quite different, more typically abstract expressionist. Of the two, I found GothamToGo (1954) to be the more interesting, different though it may be from the rest of her corpus.

Toward the museum’s rear, there is also a marvelous “Salon” section featuring paintings, prints, and works on paper that are smaller in scale and might have been in Paris’s galleries during this same period. It was there that I came upon a small gouache painting that immediately drew me in with its warmth and sense of humor. I stared but could not guess the artist. No painter’s name came to mind. Then I looked at the placard: George Morrison. This was the work of a long-forgotten professor with whom I studied at Cornell. Morrison was an American Indian from the Band of Ojibwe. I remember him as a great teacher, full of life. The piece in question, Overcast (1958), is filled with colored shapes that move rhythmically with an inherent order. Zigzags of orange keep the rhythm going across the picture plane.

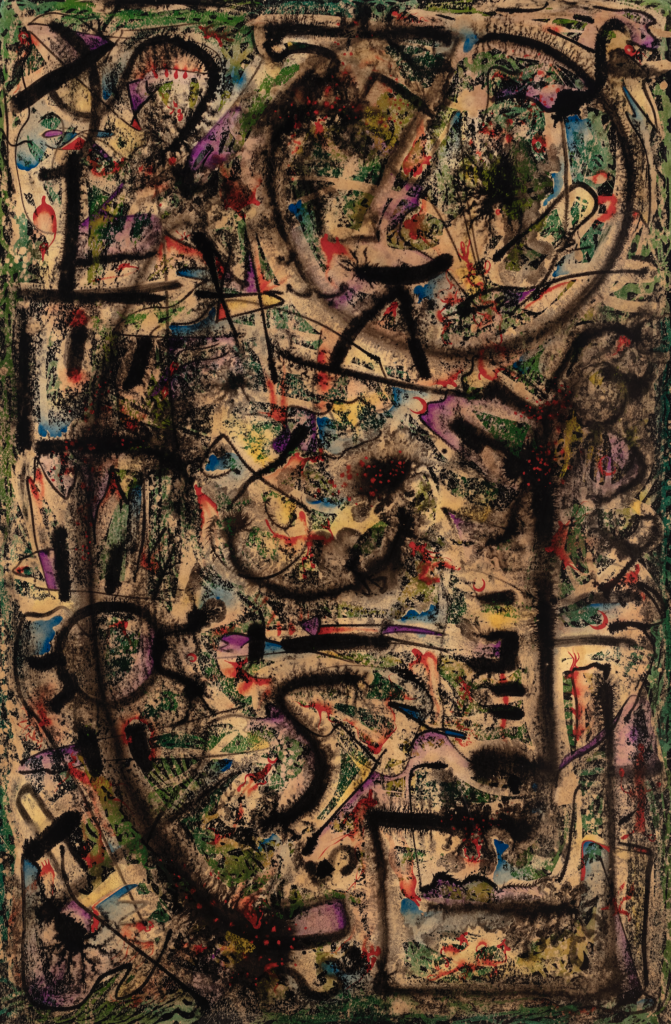

There was also in this section a mysterious Alfonso Ossorio work on paper, The Garden (1952), done in ink, wax, and watercolor. It shows delicate map-like shapes over large playful black marks, some of which look like strange letters perhaps influenced by Klee, and some of which are arbitrary. Despite this strange approach, the whole picture works. I hadn’t known Ossorio was in Paris during this period, nor that it was he who arranged for Jackson Pollock’s first show there, in 1952.

This exhibition flows smoothly and logically. The accompanying huge, information-packed hardcover catalogue is a must-buy. And what a wonderful opportunity it was spending time with so much art that rewards seeing.