Alone in a room

On a day in the artist's studio

Published in The New Criterion, December 2023. Adapted from the forthcoming memoir MERCER GREENE WOOSTER: A Life in Art, by Pat Lipsky.

It’s around 9:30 and I’m walking up Tenth Avenue to my studio on West Twenty-sixth. The building that houses it started out as a book-binding firm by the name of Wolff, which is still printed in stone over the first set of front doors. In fact, in the 1950s and ’60s, the whole block between Tenth and Eleventh was given over to bookbinding. The second entrance, the one I take, is in the middle of the block and has big glass doors. They lead into a nondescript lobby where there’s a small elevator, the slowest in Chelsea. Khan sits patiently inside waiting for the next passenger. He takes me up to ten.

My big, high-ceilinged studio at the end of a long corridor faces south. Entering it, the first thing I experience is silence. (Especially in contrast to the noise I just heard walking over.) The second is privacy. Because my name is on the door, no one can enter unless invited. Nor is the large room a part of something else — a house, a school, an apartment. It’s only for me to work in. A moment of great happiness in my later life was pasting the letters of my name onto the door of room 1011. They’re still there, exactly where I put them in 1998.

The room is white. At the far end there is a wooden painting rack where all my A-level pictures are kept. Everything I need to work — paint, sponges, jars, cans, brushes — is on a large, wooden table just where I left them yesterday.

It’s said that for years Giacometti kept things stationary in his Paris studio — which he called “the prettiest and humblest of all” — because anything moved might hinder his ability to make connections. No one was even allowed to dust. Over time my space has evolved into a studio that represents me. Photographs, postcards, and little drawings hang along one wall: my ancestors dating back to 1880; shots of my mother and father at different ages; friends and mentors; our old house; and postcards of the paintings I’ve seen and loved. Sometimes I add to these, but not too often.

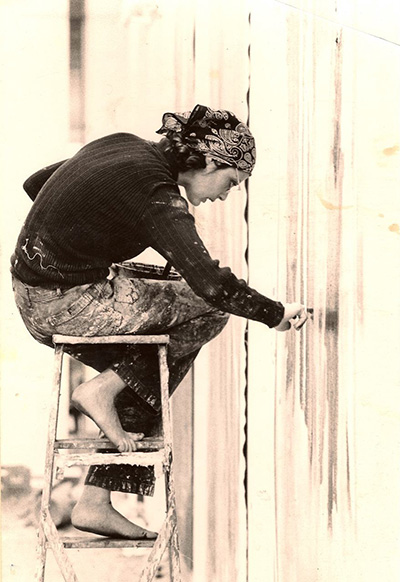

The first thing I do is take off my street clothes — replacing them with paint-splattered jeans and a similarly covered shirt, plus paint-encrusted tennis shoes. Those early twentieth-century photographs that show a suited — always male — painter sitting at an easel have to be staged. Even in a smock no one could stay that neat.

If my glass palette — white paper is kept under it so mixed colors can be seen against white — wasn’t cleaned yesterday, I scrape it with a new single-edge razor blade. Next, I do a brush check, making sure all paint residue has been removed. If not, I wash the brushes again in a slop sink behind the painting rack. Then I put on blue plastic gloves and start.

The last canvas I worked on is turned facing the wall. I carry the picture over to some old, white gallon cans on the floor, place it on them, and lean it against the wall. Then I step back and look. When I left yesterday it seemed terrific — the fruit of a whole day’s work. Now it’s not holding up. Is it the morning light?

I don’t remember exactly why it looked successful to me before. But for painters this delusional phase is a common occurrence. To be enthusiastic and positive — perhaps in order to paint at all — one needs to get carried away. But a good night’s sleep brings objectivity, and the next day I can actually see the picture. Matisse said, “Enter the painting at its weakest link.” Easy. I look for the color that’s not working and start there.

Oil paint comes in shiny tubes that are squeezed like toothpaste until nothing is left inside. Larger-than-life-size canvases like mine require lots of tubes. White, which is used for mixing, comes king-size. Because oil paint is inherently viscous, half my time is spent mixing it to a smooth consistency.

I squirt some colors onto my palette and start blending them with a palette knife. After I get a good mixture it’s scooped into a pint-size plastic delicatessen container and then mixed with a big wooden — the same type Willem de Kooning showed me in his Springs studio — until the color is the consistency of light cream.

I test this on my canvas, just a tiny dab to see if it works in context. The thing is to get the different colors carrying their own loads. (You don’t want a color overwhelming its neighbors.) If the mixture doesn’t pass muster, I add a little of this, a little of that, then dab it onto the canvas again. Usually there are several attempts before I’m ready to brush the new color on, for which I use a three-inch pig’s-hair brush. The goal is a smooth, uninflected surface that doesn’t show any “hand” — like early Netherlandish painting.

Again, I step back to look. All day — back and forth — the painter’s dance.

Throughout the process there’s always the problem of seeing. It’s tied up with everything you know and all about taste. What I’ve learned is that no one sees the same. The repository of images in our brains since birth influences our responses to all visual stimuli. (An easy example: if you know Cubism, an African mask will look more familiar to you than if you don’t.)

Different moods influence how we see. Which is accurate — the first, fresh view, or the knowing later one? Another question: is the eye a muscle that you can develop over time or simply a stable organ that depends on the brain’s interpretation? My eye doctor confirmed the latter, explaining that once a signal reaches the visual cortex it is translated by the brain to create an image.

It’s about seeing and judging (what Kant called “judgments of taste”). Jackson Pollock tried to break out of judging entirely by painting on the floor. He said,

On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting.

But then in the end he sought judgment from his wife, Lee Krasner. His question to her wasn’t “is it good?” but “is it a painting?”

Once I’ve put the colors on, because it’s abstract I can turn the painting in any direction. Now I go one rotation to the right. Like a kaleidoscope, the picture looks different with each orientation. I never decide which side is the top until the picture is finished. And sometimes even years later I might change it. Since art is all about result, the direction the painting works best in is the right one.

I reach for my Japanese Nichiban tape. It’s translucent and comes in quarter-inch, half-inch, and one-inch rolls. It doesn’t stick to the paint surface the way other tapes do. New York Central was the only store in Manhattan that carried it, but since they closed two years ago I’ve had to import it from Japan. I run tape along one edge. Then, to protect it, I cover the canvas near where I’m going to apply fresh paint with strips of Bounty paper towel. Again, I drag the paint-laden brush over a section of canvas. Then I reach for my box of skinny Q-tips. They’re not sold in pharmacies but come from a medical-supply factory in Maine. I first saw them in the fifth-floor conservation studio at the Morgan Library. The conservator told me where I could buy them. Each Q-tip has a long, thin wooden handle with a cotton swab on its end. I use this to blur the edge I just painted.

My back is starting to hurt so I lie down on a Styrofoam roller. There’s no clock in the studio, but when it feels like about ten minutes have passed I get up, wash my hands and brushes, and continue.

“Enough on the first picture,” I think. Sometimes I actually put up my right hand like a traffic cop and say out loud, “Enough, Pat, stop.” The hardest thing in abstraction is knowing when to stop. When is it enough, and when is it too much? The kind of questions Aristotle asked about everything: too much, too little, the right amount? Even in ancient Rome, Pliny the Elder complimented artists “who know when to take their hand from the picture.”

If I go too far, there’s always a risk of losing it. In writing you can go back to an earlier draft. Not so in painting, where each layer obliterates the one underneath.

So I turn that canvas to the wall and grab a smaller one. It fits flat on my forty-eight-inch table. To see it, I sit down on the top of a six-foot ladder. The color looks a little tepid, so I climb back down and start mixing Cadmium Red Medium and Titanium White with a touch of Ivory Black. Then I dab that onto the canvas where it might go and climb back up to look down again.

All these supplies — colors, tape, brushes, sponges, tape measures, Q-tips — are essential. I can’t paint if I’m missing any one of them because they’re not interchangeable. If I think a color must be middle red, I need that medium shade of red. If it has to be an off-green, I need Terre Verte. It’s said that Picasso, when he was painting in Montmartre, would use green if he didn’t have red. I can’t do that. For me colors are like people.

I don’t write down the mixtures either, the way that the color guru Josef Albers did (recipes neatly written on the backs of his masonite panels). I tried doing that, but the pieces of paper fell on the floor or got spilled on. Then too, how could I characterize the amount — “a little?” So I remember the mixtures. That’s why I keep working on the same canvases pretty consistently. During a particular time there’s a familiarity I develop with each palette that makes it sort of a color diary.

Sometimes people bring me technical books about color. I like the ones that are historical: how pigments were developed in a given century, what the meanings of colors were in different cultures. The ones that encourage the use of a color wheel are of less interest.

Paul Klee said, “Color and I are one. I am a painter.” Later Hans Hofmann wrote that successful paintings have their own “color-worlds.” Cézanne’s late landscapes of Mont Sainte-Victoire have that, a blue/green/ochre/ rust quality that transcends words.

Like numbers, colors are infinite. One could spend her whole life breaking down any one color and never come to its end. The names of colors, though, are arbitrary — like the rose they could be called “by any other name” and remain the same. It might take four ups and downs on the ladder finally to get a red that “clicks,” which I then paint on the canvas. That’s all, and the painting is turned face-to-the-wall to look at tomorrow.

Time for lunch. Even with plastic gloves on, my hands are dirty because I keep taking them off. On a bathroom trip I notice paint on my face, mostly blue. I wash it off with soap and water. Lead poisoning, which I once had, can come from skin absorbing oil paint.

In 1998, when I moved in, there was a big view of the Hudson, but over the years construction has whittled it down. Still, on the remaining sliver of river, I might see a boat or two glide by.

I’m feeling calmer than when I arrived — more in tune with myself. Through a sort of alchemy that turns base metals into gold, my tension and anxiety have oozed into the pictures. With the exception of noise, not much can bother me now. But there’s a lot of that around, constant drilling, sawing, beeping, hammering. It can start up at any moment.

I keep working until it is about four in the afternoon. The studio is a mess, stuff has fallen to the floor, and there’s a lot of soiled paper towel everywhere. Used skinny Q-tips lie around like wooden pick-up sticks. I wash my brushes again and scrape the glass palette clean for the last time. Then I sit down for a moment with my legs up on the desk. Suddenly it feels claustrophobic in the studio. My two best moments are entering in the morning and leaving in the late afternoon.