University of Iowa Press

Praise for Brightening Glance

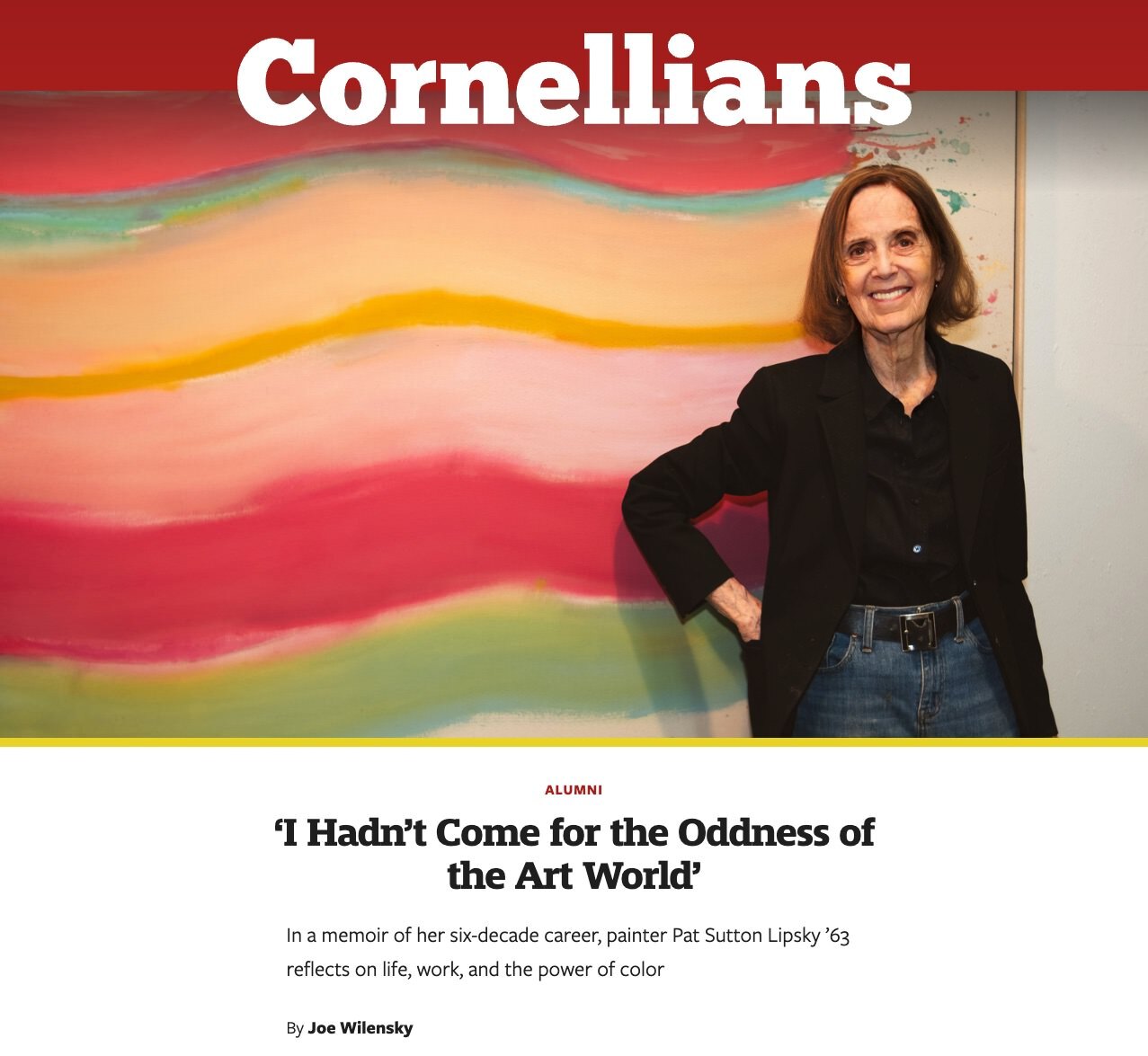

“A portrait of the artist as a woman working and living in the heart of the downtown New York art world. Pat Lipsky’s book is a stylish, entertaining, and, above all, honest memoir of a painter’s life and times. If you wondered what it would really have been like to be an artist in the years when art was all about art, this book opens the door.”

—Louis Menand, of The New Yorker and Pulitzer–Prize winning author, The Metaphysical Club

“How did Pat Lipsky pull off the near-impossible feat of breaking into the hyper-macho downtown art world? She tells us in Brightening Glance. With this memoir, Lipsky proves that she’s as brilliant, energetic, and brave a writer as she is a painter.”

—Lili Anolik, author, Didion & Babitz, contributing editor at Vanity Fair and Air Mail

“Here is an artist memoir of SoHo grit and thrown punches, of bad divorces and career reversals. What sets Brightening Glance apart is the sensitivity of its observations. A praised abstractionist on canvas, Pat Lipsky on paper proves to be a sensitive portraitist, with an astonishing command of the figures who surrounded her. Tony Smith, Lee Krasner, Clement Greenberg, Andy Warhol, Robert Smithson, and Pierre Rosenberg, among many others, leap off the page in this bittersweet and at times challenging depiction of art, love, and life.”

—James Panero, executive editor at The New Criterion